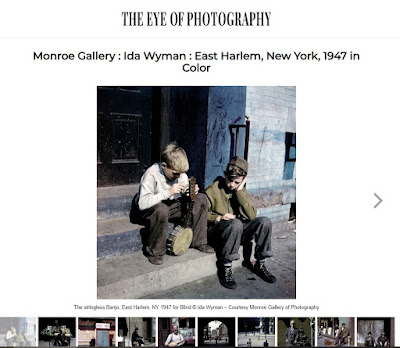

Malcolm X takes a photograph of Cassius Clay -- who was about to announce his conversion to Islam and his new name, Muhammad Ali -- on February 25, 1964 in Miami. Malcolm X was staying at The Hampton House Motel, where he spoke with Ali, singer Sam Cooke and football star Jim Brown. The photo was captured for LIFE magazine by Bob Gomel.

Photo: photo by Bob Gomel used with permission

Via The Houston Chronicle

By Andrew Dansby

February 1, 2021

Near the end of the film “One Night in Miami,” Cassius Clay — hours after defeating Sonny Liston and declaring himself king of the world … and so pretty — holds shop in a small diner at the Hampton House Motel over a bowl of ice cream.

“I want a picture with Malcolm!” he says, referring to Malcolm X, who had advocated for the boxer’s conversion to Islam, which yielded a new name: Muhammad Ali.

The film follows Malcolm X for a meditative moment. A dangerous power struggle was in place amid the Nation of Islam, and he had only one year to live. But Clay, in that moment, got his photo.

Life magazine photographer Bob Gomel — the only member of the media inside the diner — caught the champ at the counter, a look of feigned surprise with Malcolm X leaning on his shoulder seemingly enjoying the moment of celebration.

Gomel captured several enduring images from the fight and its aftermath. One included Malcolm X behind the counter taking a photo of a tuxedo-clad Ali. That iconic photo has been acquired by the Library of Congress. Both the photo and the evening have taken on significant cultural weight. The fight and the meetings that followed were caught on film by Gomel and have been written about in biographies of Ali, Malcolm X and Cooke. That one night has become almost mythical, as it saw the rise of a cultural icon in Ali, lending itself to a play that would become a film.

As for Gomel, he’d made a fleeting moment permanent, something he’d done before and would do many times later as a storied and celebrated photojournalist whose work covered presidents and presidential funerals, Olympians in action and the Beatles on a beach.

“I’d suggest the challenge is to do something better than had been done before,” Gomel says, “That was something instilled in me early in my career. When I was just starting my career, I had an editor at Life. I came back and said some event didn’t happen. And he said he didn’t ever want to hear that. After that, I never batted an eye about doing what it took to get a photograph.”

Film on film

David Scarbrough, a professional photographer, met Gomel through mutual friends and colleagues. He’s been in Houston for more than 20 years; Gomel moved here in 1977.

Any time the two would meet, Gomel would share his stories about working at Life from 1959 to 1969. Gomel resisted the idea of putting down those stories as text to accompany the photos in a coffee-table book. So Scarbrough pitched the idea of a film.

“I convinced him to do a proof of concept, and if he didn’t like it, we’d drop it,” Scarbrough says.

Using two iPhones and a makeshift sound studio behind his house, Scarbrough got Gomel to tell the tales behind some of his most famous photos.

Those interviews became the basis of “Bob Gomel: Eyewitness,” available to stream on Amazon, in which the photographer narrates his career, a mix of his photographs and his on-camera commentary. Occasionally, Scarbrough throws in an outside image, as from the first Ali/Liston fight. When Scarbrough called up the fight on YouTube, he thought he saw a familiar face in the bedlam that followed Ali’s win.

“I blew it up, and it was grainy, but there’s Bob on the other side of the ring, climbing the ropes to get the shot. I had to work that in.”

That shot becomes part of a theme throughout the film. Gomel discusses his terror shooting Olympic bobsledders from a bobsled. He is photographed in a wetsuit immersed in a pool to capture a swimmer doing the butterfly. Gomel’s photo presents the swimmer as a human wavelength, her body contorted in a way both beautiful and grotesque.

One of the most fascinating passages includes two presidential funerals. From an elevated space, Gomel photographed President John F. Kennedy’s casket in the Capitol rotunda in 1963. His image is haunting for the light beaming across the rotunda. Gomel that day made a mental note that a direct overhead photograph in the rotunda could be striking. When President Dwight D. Eisenhower died six years later, Gomel rigged a camera directly overhead.

“Everybody knows that photo,” Scarbrough says. “It was a significant moment captured by a well-executed photograph. But people don’t know the preparation to get the picture. The hours and hours of testing. This was before our digital age. You had to string the camera out, bring it back, test lenses. The prep work was incredible.”

Gomel had another concern. “I prayed my lights didn’t start flashing before the event.

“I always draw a distinction. I say you can take a picture or you can make a picture. My objective was always to make pictures. To have some idea of what you’re trying to achieve and then figure out the best way to do that.”

Life behind the camera

Gomel grew up in the Bronx, where his interest in photography began when he was still in grade school. He delivered groceries to make money for his first camera and set up a darkroom in his parents’ home. He earned a journalism degree from New York University before spending three years stationed in Japan as an aviator in the Navy. He says landing planes on an aircraft carrier created a certain fearlessness.

“I’ve never considered safe spaces when I’m working,” he says. “I’d stand on the struts of a helicopter and make sure my wide angle lens cleared the blades. But it never occurred to me to be concerned. A safety strap to the cockpit wall was all I needed.”

He was hired by Life magazine in 1959, “a childhood dream,” he says in the film.

Life at the time had a sterling reputation for its photojournalism. Gomel shot heads of state, athletes and celebrities.

The rush of images that passes in “Bob Gomel: Eyewitness” is astounding for both the richness of the individual photographs and the breadth of Gomel’s work. The photographs clearly stand alone, but the narratives that accompany them offer enrichment through context. A bust of a session with President Richard M. Nixon was salvaged a day later when Gomel returned with some brighter neckties. He also discusses his paintinglike photograph of Manhattan at night during a 1965 blackout, thought to be the first double-exposure image published as a news photo.

In the 1970s, Gomel began doing commercial photography, which led him to Houston. He’d worked closely with an advertising executive at Ogilvy who set up an office in Houston in the early 1970s when Shell relocated from New York.

“I came on a lark, and I liked what I saw,” he says.

He has made Houston his home ever since, working here and sometimes dispensing tough love to students. Long ago he hired now famed photographer Mark Seliger — who at the time was about to graduate from the High School for the Performing and Visual Arts — as an assistant.

“A month or two later, I fired him,” Gomel says. “He was too good. I told him to leave Houston and go where the big action was taking place. Fortunately, he took my advice.”

Back to Miami

Seliger is the sort of photographer who might typically appear in a documentary about an old master like Gomel. But Scarbrough had only completed the interviews with his subject when the pandemic shut down his work. So he let Gomel’s stories and his photographs tell the story, which he distributed through Amazon Video Direct.

After a short introduction, the film moves to February 1964, when Life sent Gomel to Miami and assigned him to Clay before he became Ali. Liston was favored 7-1, but Life wanted a Clay cover photo ready should he provide an upset.

Days before the fight, Gomel caught a sweat-soaked Clay smiling. The fight took place Saturday. By Monday, Gomel had a magazine cover.

But the aftermath of the fight proved interesting, too. Because he was assigned to Clay, Gomel traveled with the boxer’s entourage — which included Clay’s brother and Malcolm X — to the Hampton House in Brownsville because no South Beach hotel would accept Black guests.

Playwright Kemp Powers debuted “One Night in Miami” seven years ago. Powers was drawn to a meeting that took place after the fight, when Malcolm X, Clay, singer Sam Cooke and football star Jim Brown gathered in a room at the Hampton. His story, an imagined account of their conversation, springs from four prominent Black men at personal, vocational, cultural and spiritual crossroads. Clay would soon announce his new name and faith; Brown would leave the NFL for film; Malcolm X and Cooke would both become victims of violence.

Late last year, actor and filmmaker Regina King presented a filmed version through Amazon. The film plays with the timeline, flipping the sequence of the diner and the hotel room meeting. It also re-creates that scene from Gomel’s photo: Malcolm X behind the counter, camera in hand.

Gomel expresses frustration that nobody involved with the film reached out to him for licensing or even a credit. He resisted Life’s offers of insurance and equipment allowances to have rights to his photos revert back to him.

Re-creation of photographic moments isn’t unique to “One Night in Miami”; Netflix’s “The Crown” — to name just one TV show — is teeming with shots based on photographs.

Gomel has dealt with the issue before. He’s found the image on T-shirts, throw pillows and earrings.

“It’s new dealing with organizations that don’t do the right thing and contact you,” he says. Gomel recalls the estate of golfer Arnold Palmer securing a photo Gomel took for Palmer’s clothing line.

“That’s the way it was for 50 years,” he says. “People respecting traditions.”

So “Eyewitness” provides the story behind the photo behind the film.

“Just about everybody else in that context is long gone,” Gomel says. “I’m one of very few eye witnesses who was actually there.”