Friday, February 12, 2021

Friday, December 18, 2020

"Bob Gomel has been a witness and participant in it all, albeit with a front row seat to history and the perspicacity of a seasoned observer."

Bob Gomel was the go-to photojournalist for LIFE magazine in our state in the 60s, covering The Beatles on their first U.S. tour and then Cassius Clay on the night that he became Muhammad Ali.

Via Naples Florida Weekly

December 17, 2020

By Evan Williams

PHOTOGRAPHY HAS LONG BEEN A mass medium, but absent the cost of developing film or making prints, the digital revolution allows people now to practice it almost as freely as writing. Debates continue to percolate about the qualities of a phone camera compared to compact cameras and more expensive tools of the trade, with a resurgence of film formats that counter a growing digital revolution, not to mention the social ones.

Bob Gomel has been a witness and participant in it all, albeit with a front row seat to history and the perspicacity of a seasoned observer. A photographer for LIFE magazine from 1959 to 1969, his iconic images of presidents, sports stars and mop-topped pop singers are among many others in a storied career.

In October on a webinar in Houston to announce a new documentary about his career, “Bob Gomel: Eyewitness,” he was asked about the equipment he has been using and how technology has made the art form more democratic than ever.

The Houston, Texas resident, age 87, shoots digital these days.

Photographer Bob Gomel covered The Beatles’ first appearance in the United States, capturing this photo of Paul, Ringo, George and John in Miami Beach in 1964. COURTESY PHOTO / © BOB GOMEL

“I think talent will prevail,” Mr. Gomel said. “There is a lot more competition out there and a lot more outlets (for photographers). But there are still exceptionally wonderful examples of the best photojournalism available, and I see every day pictures that I would have been proud to call my own. The technology allows more capability perhaps than we had with film. However, it is still the mind of the artist that is the governing factor, not the equipment.”

He added that a well-known writer he had worked with once asked him what type of camera he was using.

“I answered him by saying I had read his most recent article and I was curious about what typewriter he used to tell that story,” Mr. Gomel said, “and I think he got the point right away.”

Some of his favorite photographs appear in his old hometown paper, The New York Times, which he still reads regularly, and National Geographic. Mr. Gomel spoke more about his life and career with Florida Weekly on a phone call in October.

Photographer Bob Gomel traveled with President Kennedy and his inner circle along the Florida coast, making this image. COURTESY PHOTO / © BOB GOMEL

End of an era

In a pre-internet world, the gushing firehose of content that floods our sightlines on social media now was narrowed to a relative handful of prestigious print newspapers and magazines: the gatekeepers of content and culture in the 20th Century United States of America.

The era was a world of its own. And when it came to photojournalism, LIFE magazine was at the pinnacle, even if photojournalism was shunned by fine art galleries. That line still exists even as it continues to blur.

“The entire journalistic landscape has just changed dramatically since that era,” said Sid Monroe, co-owner of the Monroe Gallery in Santa Fe, N.M., which has mounted several solo and group exhibitions of Mr. Gomel’s work.

“You had institutions in that time like LIFE and even Walter Cronkite for the TV news, they were just seen as the towers of information. It is almost like rolling all the social media into one package because (LIFE) covered politics, it covered disasters, it covered if there was a hurricane, if there was a society wedding; it would cover the latest Hollywood movies, it would cover the Royal family; and it would go to the ends of the earth to cover stories that normally people wouldn’t be exposed to.”

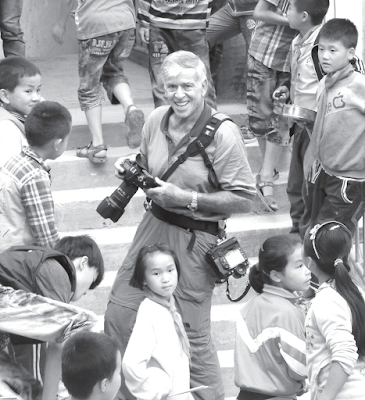

Photographer Bob Gomel remembers covering events in Florida, and discusses his experiences in the documentary “Bob Gomel: Eyewitness,” available on Amazon Prime for viewing. COURTESY PHOTO / © BOB GOMEL

The San Francisco Chronicle reported that Mr. Gomel is among fewer than 100 men and women who worked for the weekly magazine during its heyday, from 1936 to 1972. LIFE is now an online only archive.

Mr. Gomel jokes, but truthfully, that the average age of a LIFE staffer these days is “deceased.”

“It’s the end of an era, a very wonderful era,” he said.

The job at LIFE was as competitive and demanding as you might expect. In the 1960s, Mr. Gomel traveled with President Kennedy and his inner circle along the Florida coast, visiting Cape Canaveral, before later ending up at Rice University in Houston.

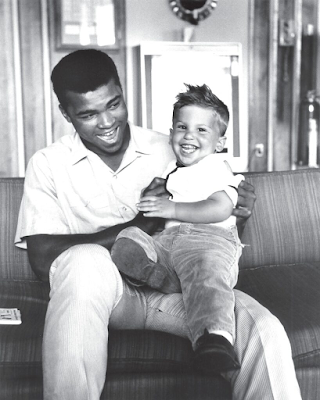

Photographer Bob Gomel became friends with boxing legend Muhammad Ali, who he found to be funny and gracious. He is shown photographed here with Gomel’s son Corey as a toddler on the boxer’s lap. Many of his photos ran on the covers of LIFE, Newsweek and Sports Illustrated, below. COURTESY PHOTO / © BOB GOMEL

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard,” the President famously said there.

Mr. Gomel recalled the scene when JFK would get off at a local stop along the way.

“So I’m three feet in front of the President, walking backwards,” he said, “and the local guys are saying, ‘give us a break.’ But I couldn’t do that because God forbid something happened in that moment and I missed it. I certainly respected my fellow professionals but I didn’t give any ground either. I felt obligated to stay, to the best of my ability.”

In August the year after President Kennedy was assassinated, Mr. Gomel found himself at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, N.J., photographing the keynote speaker, Senator John O. Pastore of Rhode Island. In doing so, he blocked the view of an annoyed spectator and famous actor.

“I was just a few feet step down from where (the Senator) was and I wouldn’t take my eye off him for one second, looking for a great expression,” Mr. Gomel said. “And who was sitting behind me but Paul Newman. And he said, ‘sit down already, get out of my sight,’ and I did not. And Newman ended up throwing his program at me. I still didn’t back off … It might seem callous and rude and an amateur wouldn’t do that. But my boss at LIFE said to me one time early on in my career he didn’t want any excuses, ‘come back with the picture.’ And I never forgot.”

His picture of Senator Pastore later won best news photo of the year from the University of Missouri School of Journalism.

In Miami

February 1964: LIFE sent Mr. Gomel from his Long Island home in Merrick to Miami to photograph The Beatles during the band’s first appearance in the United States. Nine days later, he was watching Cassius Clay (Ali) make good on his promise to “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” as he beat Sonny Liston to win the heavyweight boxing title.

On Feb. 16, The Beatles performed in front of more than 70 million viewers for The Ed Sullivan Show at the Deauville Hotel in Miami Beach — a reprise of their U.S. television debut on the show in New York on the Feb. 9.

Mr. Gomel photographed them in the days that followed, first at a private residence with a pool. The Beatles were in their early 20s, pale, skinny and uncertain, but enjoying Florida with its balmy weather and palm trees.

“That was just like paradise because we’d never been anywhere with palm trees,” Paul McCartney says in a video from the time on YouTube.

The most well-known Bob Gomel picture of The Beatles depicts the four lads in chaise lounge chairs catching some rays.

“They were very willing to cooperate finally when we got to the pool and they wanted to know what to do,” Mr. Gomel said. “So my reaction was ‘go have fun,’ and that’s exactly what happened. And I found myself just recording them doing cannonballs and silly things.”

The next day they headed for North Miami Beach for another shoot.

“It was chaotic,” he remembers. “We thought we’d go in an area where they had some peace and quiet. But these young ladies spotted them and pretty quickly a crowd formed and it was mayhem until escorts, police escorts were able to extricate them and get them back to the hotel. But it was a fun experience, and I was very moved by that phone call many, many years later from one of the young ladies’ parents.”

That young lady was Ruth Ann Clark, age 16 that day on North Beach when she planted a kiss on Paul McCartney’s cheek. Mr. Gomel captured the moment but those pictures would not be published for another 51 years.

“The editor of LIFE, God bless him, he did not care much for the Beatle phenomenon,” Mr. Gomel said.

Later that year, Clark moved with her family from Miami to Portland. She died in 2005 in Elkton, Ore.

Her parents were never convinced of her story about meeting The Beatles. When some of the photographs finally appeared in Closer magazine in 2015, they were surprised to find out the truth. Mr. Gomel ended up providing the family with additional photographs from that time.

On Feb. 25, after shooting the heavyweight title fight at Convention Hall on Miami Beach, Mr. Gomel traveled with the fighter and crew back to the historic Hampton House, which was in the so-called Green Book, a list of motels in the U.S. where Blacks were allowed to stay.

The party got to the hotel close to midnight, Mr. Gomel recalls, and he was the only member of the press in attendance. Ali was hamming it up and the whole crew was pushed into the hotel café, where Mr. Gomel jumped up on the counter and took his best-ever selling photograph: Ali’s close friend, Black Muslim leader Malcolm X, snapping a photo of a celebratory Ali.

“Funny things you remember,” Mr. Gomel said. “Rahmin, his (Ali’s) brother is sitting off to Ali’s left and Rahmin is having a glass of milk. I think in my frame in the far right corner there’s a glass of milk. You can’t see Rahmin, he was chopped out.”

It was in the first few hours of the next day when Mr. Gomel returned to his hotel. The picture of the two icons would later end up selling more than any of his other photographs through an art gallery that promoted the work.

But like those shots of the Beatles, LIFE chose not to publish it. A few of Mr. Gomel’s favorite shots of JFK were initially overlooked as well.

“We shot hundreds of pictures every day and they were sent up to the main office,” Mr. Gomel said, “and there was editing or deadlines and such and a lot of things were deemed not appropriate or fitting at that moment to those editors.”

He too remains uncertain why that picture of Ali and X rose to greater fame than so many other pictures in a career full of powerful and iconic moments.

“I am still hard pressed to understand why this picture outshines everything else that I’ve done from the point of view of sales.”

Mr. Gomel got to know Ali, who he found to be funny and gracious, and photographed his son Corey as a toddler on the boxer’s lap. Many years later, Corey went to a conference in Houston where Ali would appear, to get the picture autographed. This time Ali was ravaged by Parkinson’s Disease. As the family story goes, he looked at the now grownup Corey and quipped, “You still ugly.”

Woke

Mr. Gomel can pinpoint the moment in grade school when he awoke to the medium. He was looking at a picture but there was nothing overtly special about it. Just a pigeon and a manhole cover.

“It was taken by my teacher and his name I remember to this day was Mr. Fields,” Mr. Gomel said. “He was an amateur photographer, obviously, but fortunately he printed his pictures. And this particular print he referred to was sepia toned and truth be told I can see that in my mind’s eye as if I’m looking at it right now. I was smitten by the power of that image… I knew from that moment on that photography would be my calling, that’s how it started.

“On my travels these many, many years later in retirement so to speak, I found a pigeon on a manhole cover and I made that photograph. It became a full circle from the inspiration that started my (career) to finding something very, very similar in India.”

He continues to draw inspiration from many photographers. He described street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson’s iconic book “The Decisive Moment” as “one of the most exciting visual experiences I can think of.”

Some of LIFE’s early photographers also became mentors.

He recalls one lesson learned from Yousuf Karsh, a portrait photographer who took a famous picture of Winston Churchill.

With just 15 minutes to achieve the striking portrait he was after, Karsh unexpectedly reached out and yanked the cigar right out of Churchill’s mouth, Mr. Gomel said:

“Churchill’s expression was as stern as could possibly be. Now that particular photograph was the inspiration for England to persevere against that horrible bombing they went through night after night. He knew exactly what he was after and he figured out a way he could achieve those results. And that’s what I try to do before I pick up that camera.”

Getting the job at LIFE

Mr. Gomel was born in 1933 in Manhattan. His father was an optometrist and his mother taught history and civics in the New York City Public School System. He had one brother, five years his junior.

The first inklings that he was interested in images came in the form of drawing on a roll of wrapping paper that he and his mother put up in their hallway.

“I remember very clearly using pastel crayons to do the pictures of what I imaged the Pilgrims would be like, perhaps meeting the Indians, and that was my first expression of any kind of artistic interests.”

His family had one of the famous Kodak Eastman Brownie cameras, known for introducing “the snapshot to the masses,” Wikipedia says. One winter he delivered groceries to buy his first camera with full controls. His family agreed to let him turn a closet into a darkroom to develop film.

At New York University, he earned a degree in journalism in 1955. He found mentors in the New York press core at college home games at Madison Square Garden, third-shift photographers he would follow on assignment at night, emulating some of their techniques.

After college he became an aviator in the Navy, stationed in Japan on an aircraft carrier during the Korean War. On the weekends he enjoyed driving out into the country and taking pictures, but flying was frightening. It required high competency in mathematics, a challenge for the journalism major, who was behind his classmates in that regard.

“My classmates were really sharp and I tried like hell to keep up with them,” he said. “It required after lights out, I would go into the bathroom where there was still light to continue studying to keep up with these guys.

“Let me tell you this, night landings at 400 miles per hour out at sea when there is radio silence was as scary a business as exists. That whole operation caused me to be a cigarette smoker for the first time in my life and eventually a rum drinker.”

After coming home he got high-paying job offers from airlines, but he wanted to distance himself from aviation. He was determined to work for one of the picture magazines.

At the time, his brother was seriously injured in a car crash. Mr. Gomel documented his family during a time of crisis, convincing doctors at the hospital to let him in the room as they removed his brother’s lung. When he got the opportunity for an interview at LIFE, that work was strong enough that they offered him a commission to complete the story, Mr. Gomel said — the beginning of his career.

And as it turned out, after his experience in the Navy, photographing famous, powerful people for a national publication seemed almost relaxing in comparison.

Eyewitness

The director of “Bob Gomel: Eyewitness,” David Scarbrough is a photographer and owner of Expirimax, a franchise specializing in pre-owned Apple equipment and repairs.

When Mr. Gomel came in to his Houston store one day, Mr. Scarbrough didn’t immediately recognize him.

He asked a co-worker, who identified him: Bob Gomel, who has remained active in the local photography community and is a superstar to media photographers who know of him, Mr. Scarbrough said:

“He’s a good looking guy, he dresses very well and he’s got this million-dollar smile. You could tell when he walked in the room he was somebody special.”

After they became friends, Mr. Scarbrough inquired about filming a documentary to capture some of the amazing stories that would often come up in casual conversation.

“My point of view on it is the stories are as interesting as the pictures,” Mr. Scarbrough said. “The pictures are just timeless, right? But the story of the (President) Nixon portrait and the Ali thing with the kid sitting on his lap; the way he did the (President) Eisenhower funeral picture; this is groovy stuff, this is great stuff.”

The documentary was filmed in 2019. Mr. Scarbrough took a paired down approach, filming with a pair of iPhone 10s and letting his subject tell the stories behind his groundbreaking career. The film was released this year on Amazon Prime.

Picture by picture, it delves into how Mr. Gomel persevered through his approach to making momentous images at key moments, whether calling back President Nixon’s office after a botched photo shoot or his (at the time) controversial use of double-exposure to depict a 1965 blackout in New York City.

“He did what it took to get the shot and nothing was out of the question,” Mr. Scarbrough said. “That’s what I hoped to capture with this.”

After LIFE, Mr. Gomel’s work was published in Sports Illustrated, Newsweek, Fortune and the New York Times, among many other publications. He went on to focus on commercial photography for companies like Audi, Volkswagen and Merrill Lynch.

In 1977, he moved to Houston, where he lives with his wife Sandra. They have three sons, the youngest of which died at age 32, leaving behind two grandchildren as well.

Advice

This October, Mr. Gomel’s frequent travels were on hold during the pandemic. Although he suffers from atrial fibrillation, he still continues his lifelong habit of swimming, which he practiced competitively in high school and college, he said, “although not nearly with the quality and speed I had as a younger person.”

At home he found himself not shooting pictures even though he remained ready if inspiration should strike. One day he pulled out some of his cameras and recharged batteries that had been sitting idle.

“My motivation these days is all oriented around the trips that we make and that’s when I’m back in my own shooting mode with cameras around my neck,” he said. “These days it’s not the same.

“My interest is now and really always has been in the lifestyle of people, particularly those cultures that are not very well known in the general public. I had the good fortune after leaving my career as a journalist to travel to far flung places.”

He enjoys the high quality images and lighter camera bodies that technology allows these days; “The lighter they are the more I like them.”

One picture for “Eyewitness” shows him holding a new high-definition Nikon digital camera. But he often uses his phone camera as well.

“I use my cell camera quite a lot because it’s always with me,” he said. “We were (in Ethiopia) covering an important religious festival and there was so much going on that I used up my memory cards in my digital camera. I had my cell phone, and the best pictures after eight to 10 hours of shooting from early morning to darkness, I got on my cell phone. And you know what? I was able to make beautiful 16-by-20 prints from those pictures. The technology is just fantastic. Again, it’s not about the tool, it’s the person behind the equipment taking advantage any way he can.”

As an amateur photographer now, his approach is still informed by the lessons honed during his career.

“I think I approach my subjects with knowledge of what had come before, what had been done prior and previously, and wondered and thought about how I could do it better and differently,” he said. “And that basically was how I approached everything. I didn’t want to be part of the pack. I wanted something above that, at a different level.

“I wanted to always create images that would make the viewer look at them and say, ‘Wow.’”

His wife Sandra has joined him in his enthusiasm for photography and he offers some of the same advice he gave her:

“Move in close, work the situation until you have exhausted every possible thing you can think of. Don’t just take a snap and walk away but explore the angles. What about the lighting? What about the time of day or night? All those things you should explore and work until you absolutely, positively cannot think of another thing to do and then you go home and hope you’ve got it. If not, come back tomorrow and try again.”

Afterlife

Now, Mr. Gomel’s work has found new life in another context: displayed on the walls of The Monroe Gallery in Santa Fe.

“It is extremely rewarding as a gallerist to sort of be a fly on the wall as people view, enjoy, experience Bob’s photographs,” the gallery’s co-owner Mr. Monroe said. “We could do another 20 exhibits of Bob’s work and still not have shown the full range of what he’s done.”

The pictures take on new meaning in the gallery, where they loom large to be examined more closely for their formal artistic attributes as well as historical resonance.

“We have people crying in the gallery because the pictures hit you emotionally,” Mr. Monroe said. “Even if you weren’t alive in that moment you are aware of the importance of history and what was possible and what was extinguished. And that translates to so many of his pictures.”

He adds, “Just everyday pictures take on a great emotional meaning when seen in the gallery.”

The top photojournalists of Mr. Gomel’s generation were often excluded from the world of fine art compared to other image makers like landscape pioneer Ansel Adams or Helmut Newton, Mr. Monroe said. He added that for many of those old-school photojournalists, they never envisioned their work in galleries either.

“There was almost a disregard for it because it was just sort of seen as news photography or magazine photography,” Mr. Monroe said. “So for the photojournalist, it’s been a long time coming for their recognition in the art world.”

Mr. Gomel’s work can also be found at The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and in many books. Four years ago, he donated his archives, including negatives, contact sheets and prints from 1959 to 2014, to The University of Texas at Austin, Briscoe Center for American History.

Bob Gomel Eyewitness is available from Amazon Prime here.

View a selectionof Bob Gomels fine art prints here.

Tuesday, August 11, 2015

August 11, 1965: Watts

The Watts Riot, which raged for six days and resulted in more than forty million dollars worth of property damage, was both the largest and costliest urban rebellion of the Civil Rights era. The riot spurred from an incident on August 11, 1965 when Marquette Frye, a young African American motorist, was pulled over and arrested by Lee W. Minikus, a white California Highway Patrolman, for suspicion of driving while intoxicated. As a crowd on onlookers gathered at the scene of Frye's arrest, strained tensions between police officers and the crowd erupted in a violent exchange. The outbreak of violence that followed Frye's arrest immediately touched off a large-scale riot centered in the commercial section of Watts, a deeply impoverished African American neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles. For several days, rioters overturned and burned automobiles and looted and damaged grocery stores, liquor stores, department stores, and pawnshops. Over the course of the six-day riot, over 14,000 California National Guard troops were mobilized in South Los Angeles and a curfew zone encompassing over forty-five miles was established in an attempt to restore public order. All told, the rioting claimed the lives of thirty-four people, resulted in more than one thousand reported injuries, and almost four thousand arrests before order was restored on August 17.

Throughout the crisis, public officials advanced the argument that the riot was the work outside agitators; however, an official investigation, prompted by Governor Pat Brown, found that the riot was a result of the Watts community's longstanding grievances and growing discontentment with high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and inadequate schools. Despite the reported findings of the gubernatorial commission, following the riot, city leaders and state officials failed to implement measures to improve the social and economic conditions of African Americans living in the Watts neighborhood. The Civil Rights Digital Library