Via Pasatiempo

March 5, 2021

By Michael Abatemarco

Ida Wyman with two of her cameras in an undated photograph

The golden age of street photography, photojournalism, and documentary photography lasted from the 1930s to the 1950s. It was an era that saw the birth of a number of influential photography agencies and collectives, including Magnum, founded in Paris in 1947, and New York’s Photo League, founded in 1936. Many of their number were among the most respected photographers of their day, including Magnum’s Henri Cartier-Bresson and the Photo League’s Paul Strand and Arthur Leipzig.

Most of the images that came out of the era were in black and white, partly because color printing was more expensive and less stable, and most news agencies and magazines only printed in black and white. “Color negates all of photography’s three-dimensional values,” claimed Cartier-Bresson.

Stickball on St. Nicholas Avenue, East Harlem, 1947

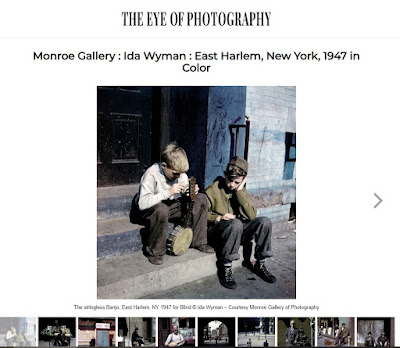

Ida Wyman: East Harlem, 1947 in Color is a selection of 14 photographs on exhibit at Monroe Gallery drawn from a series called Lost Ektachromes. The photographer, who was a member of the league, came across the negatives sometime around 2010. They remained undeveloped until then because Wyman, who was proficient at printing in black and white, lacked the expertise to do her own color printing. She needed to find someone she could trust who could print them with fidelity and under her supervision.

“She was already in her 80s,” says Wyman’s granddaughter Heather Garrison, who manages the estate. “She always said she wanted to do an exhibit on this work. And as we catalogued it, we found additional pieces.”

Wyman (1926-2019) was “no slouch,” says Michelle Monroe, co-owner of Monroe Gallery of Photography, adding that she shot more than 100 assignments for Life magazine throughout her career as a freelance photographer. Her work exemplified the cooperative’s focus on capturing the human condition in America’s urban and rural settings at mid-century.

“It was really one of the first movements to use photography as a social documentary tool,” says gallery co-owner Sidney Monroe.

The work in the show includes portraits, street scenes, and candid images of people. Some are street vendors selling their wares. Some sit on stoops engaged in conversation, and some are merely walking or otherwise going about their day. As a whole, it’s a simple snapshot of life in the city.

The Key Maker, East Harlem, 1947

East Harlem was a neighborhood of immigrants and the working class poor. As a photographer, she had an ethos in line with that of the Photo League, although she was not yet a member at the time the photos were taken. And none of them were shot as an assignment but purely to indulge her own enthusiasm for the medium. Wyman was also experimenting with a new kind of film. Ektachrome was only developed in the early 1940s. The work languished in her archives, in part because Wyman never achieved the notoriety of her contemporaries until late in life, and she was never focused on showing her work publicly in galleries or museums.

“Ms. Wyman — whose work for Life, Look and other magazines went largely unheralded for decades — discovered what she called a ‘special kind of happiness’ in photographing subjects like a little girl wearing curlers, a peddler hauling a block of ice from a horse-drawn cart and four boys holding dolls, pretending to be the plastic girls’ fathers,” wrote Richard Sandomir in Wyman’s New York Times obituary (“Ida Wyman, Whose Camera Captured Ordinary People, Dies at 93”). Perhaps that’s because Wyman, like many of the subjects she photographed, came from a working-class family. Her parents were Jewish immigrants in Malden, Massachusetts, who later owned a small grocery store in the Bronx.

Soon after graduating from high school in 1943, Wyman started working in the mailroom at Acme Newspictures. Eventually, she was promoted to photo printer. Her intention was to spend a year working before starting nursing school. “She was always fascinated by science and medicine,” Garrison says of Wyman, who got her first box camera at 14. But in the interim, her love of photography superseded other ambitions.

Wyman spent her earnings on film and processing. “On her lunch breaks and in her spare time she just loved to walk the city and take pictures,” Garrison says. “Then she would have a body of work that she could show.” Determined to land assignments, she reserved these bodies of work to show to editors.

Wyman had no job security at Acme. When the men came back from the war, Wyman and women like her were out of a job.

However, her career in photography was just beginning.

The Shoe Shine Man, East Harlem, 1947

Over the course of the next six years, she worked as a freelancer, taking assignments for Fortune, Look, Life, and Parade, among other publications. “She had the usual soft assignments, like for the Saturday Evening Post,” Michelle Monroe says. “If there was a grocery store opening, ‘send the woman.’ She wasn’t picky. She wanted the work. I think it was very hardscrabble working as a woman without the affiliation of a publication directly.”

But Wyman was motivated. Garrison says she landed assignments through sheer perseverance. “I give her a lot of credit, a young girl — 18, 19, 20, 21 — especially in a man’s world, walking into these offices and self-advocating,” Garrison says.

Wyman was encouraged to join the Photo League on the advice of her husband, photographer Simon Nathan, but in the early 1950s, the demands of family life temporarily curtailed her career. When she returned to photography in the 1960s, it was as a photographer in medical fields. She was chief photographer at the department of pathology at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons from 1968 until 1983 when she returned to freelancing.

“Her varied assignments always focused on human interest stories, which have become a hallmark of her work,” Garrison says.

That’s what we see in her black-and-white photographs, but also in the Ektachromes. And like her monochromatic work, the contrasts are stark, the shadows deep and rich, befitting, perhaps, the work of one who’s not used to shooting in color. The palette is muted, giving them the appearance of hand-colored photographs, a technique that was common since the early days of photography. And they weave a similar kind of nostalgic spell. But unlike hand-coloring, their ethereal and dreamlike quality, says Michelle Monroe, was due in part to the city’s pollution.

The stringless banjo, East Harlem, 1947

“Most cities in, say, like the 1920s through the 1960s, were powered by coal,” she says. “There’s a lot of diffused light. Coal hung around the lower city so much. There’s such a softening of the air from that particulate. Margaret Bourke-White taught us that — not directly, but in studying her work.”

But it’s the joyous aspects of the familiar and the sense of commonality that also make them captivating.

“She always had an eye for people,” Garrison says. “She loved to connect with people, and I think that’s what made her photos so wonderful.”

details

Ida Wyman: East Harlem, 1947 in Color

Through April 11

Monroe Gallery of Photography, 112 Don Gaspar Ave., 505-992-0800, monroegallery.com