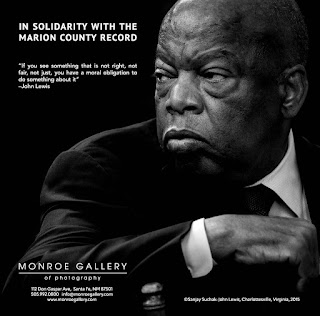

Remember the raid on the Marion County Record last August? There are several updates as the "investigations" are still ongoing.

Via Freedom of the Press Foundation:

Investigations into the raid

are ongoing and

news continues to

emerge about additional evidence of Marion officials’ retaliatory motives for their actions.

Last week, the Marion County Record sued the city of Marion and the officials who authorized the raid, including the then-mayor and police chief. The Record’s publisher, Eric Meyer, also joined the suit, both in his own name and as executor of his mother Joan’s estate. Joan Meyer died at age 98 the day after the raid of the home she shared with her son, likely from the stress — but not before

giving police a piece of her mind.

It’s the fourth lawsuit filed in connection with the raid, along with two by reporters who worked for the Record at the time and one by the paper’s office manager.

The Record’s

lawsuit contends that the raid was not the product of mere incompetence by a small town police department but a coordinated effort to retaliate against the paper for its coverage of local politics.

In addition to the lawsuits, investigations related to the raid are still pending — both of law enforcement officers’ conduct and of whether Record reporters broke the law.

As Kansas media lawyer Max Kautsh recently

wrote for the Kansas Reflector, it’s well past time to drop any remaining investigation of the Record or its reporters.

The theory used to justify the raid – that a reporter broke identity theft laws by accessing online DUI records – is

nonsense. The federal Driver Privacy Protection Act doesn’t protect DUI records, and includes an express exemption for research. The Kansas Department of Revenue, which runs the website the Record accessed,

has said the site is open to the public. And the notion that routine journalistic conduct like accessing public records for newsgathering purposes constitutes identity theft or fraud is plainly offensive to the First Amendment.

The investigation of the law enforcement response is another story entirely. Although the probe (which, as discussed later, is being handled by the Colorado Bureau of Investigations, or CBI) is reportedly wrapping up, it’s alarming that it’s taking so long given the volume of evidence of unconstitutional retaliation. Hopefully the delay is because authorities are figuring out just how thick of a book they can throw at those responsible for the raid.

Here are just a few of the revelations that have come to light in recent months, thanks in large part to intrepid reporting from the Record itself, the Reflector, and other local news outlets, as well as from information contained in the Record’s lawsuit. Much of the news focuses on the conduct of then-Marion police chief Gideon Cody, but others, from Marion’s then-mayor to the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, or KBI, are also implicated.During the raid of the Record’s newsroom, Cody took the opportunity to rifle through reporters’ documents

about himself — even though the raid was purportedly over newsgathering about a local restaurant owner. Cody was suspended and then resigned, but he was replaced by an interim chief who also participated in the raid (as did the entire police department). Other officers directed Cody to the files about him and suggested he review them.

Rather than limiting the seizure to records related to the purported investigation,

Cody said officers should “just take them all,” because he was hungry. Cody then allegedly had a “pizza party” with the county sheriff. Meanwhile, the Record

struggled to publish its next edition without any of its files.

Cody spoke to the restaurant owner whose information the Record was accused of “unlawfully” accessing on a public website by phone between the raids of the Record’s newsrooms and the Meyers’ home. He reportedly started the call with “Hey honey, we can’t write anything,” before providing a verbal play-by-play. The restaurant owner has

also acknowledged that she deleted texts with Cody pursuant to his requests.

After the raid drew national backlash,

Cody sought an arrest warrant for two Record reporters. Two hours later, the Marion County attorney

revoked the search warrants that prompted the raids due to a lack of evidence.

The KBI, which attempted to distance itself from the raid after the fallout, was actually on board from the outset, receiving an

advance copy of the search warrant and communicating with Cody throughout the ordeal. County Attorney Joel Ensey, who initially said he hadn’t reviewed the warrants, also reportedly received an advance copy from police. Days after news of the KBI’s involvement in the raid broke, the

KBI asked the CBI to take over its investigation of the raid.

Prior to the raid, Cody allegedly

tried to persuade a Record reporter, Phyllis Zorn, to leave the newspaper and start a competitor, promising he would invest in the rival paper. Zorn is now one of the reporters suing over the raid.

Prior to the raid, then-Marion Mayor David Mayfield

allegedly reposted a Facebook post by his wife asking “If anyone is interested in signing a petition to recall [then vice-mayor Ruth Herbel] and silence the MCR [Marion County Record] in the process, let me know.”

Eric Meyer

has said that he filed his lawsuit reluctantly — not wanting to bankrupt his hometown — and will donate any punitive damages to charitable causes. His hesitance is understandable. But accountability is desperately needed. Hopefully the CBI will help provide some, and soon.