Via The Independant

Wednesday 11 July 2012

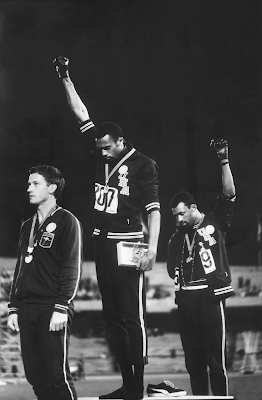

Tommie Smith's salute is recalled in a new film

The veteran sprinter is reminiscing about just what it feels like to go to

the blocks in an Olympic final. He makes it sound like a dead man's

walk.

It is certainly traumatic, it is certainly traumatic," the sprinter repeats

the phrase. "You know, looking around, walking in a stadium is an experience

that only those in the field can feel. You work all these years competing

against some of the best people in the world and then you get to the final race.

It goes beyond human imagination to the point where you forget where you are and

you go back to your childhood, thinking 'how did I get here?' You look around at

these world-class athletes and if you're not very careful, you can lose your

race before you start by thinking everybody else is better than you are and what are you doing

here?"

Whatever the state of his nerves, the sprinter in question ran an immaculate

race. He whipped past the finishing line of the 200 metres final at the Mexico

Olympics in 1968 in an astonishing time of 19.83 seconds.

Tommie Smith was 24 at the time, younger than Jamaican champion sprinter

Usain Bolt is now. "Aged 24, my speed and Usain Bolt's speed were about the

same," Smith says today. The assumption was that he would get even faster.

However, when he and third-placed fellow African-American athlete John Carlos

went to the podium, they raised their fists in a Black Power salute. The gesture

caused outrage at the International Olympic Committee, which dubbed it a

"violent breach" of the Olympic spirit. Smith and Carlos were vilified, as was

the white Australian silver medallist Peter Norman (who supported their

gesture.) The story of the friendship between the three men is told in the

documentary Salute, shortly to be released in the UK.

"He [Norman] was a man of his word and a man of honesty." Smith pays tribute

to the Australian sprinter. "He believed in rights for all men. He was a true

friend and he went through some of the same things that Carlos and I did," Smith

remembers of how all three men suffered because of their gesture in support of

human rights. Norman didn't raise an arm but he wore an "Olympic Project For

Human Rights Badge" –itself a defiant act – and he suggested that Carlos should

wear Smith's left glove. As a result, he was ostracised by the Australian media

and the country's Olympic selectors, who never picked him again.

After Mexico 1968, Smith's own Olympic career was over. If he is bitter about

the way he was treated by the Olympic movement, he is not showing it. He

relishes the friendships that the Olympics can help foster between athletes all

over the world. However, he has no illusions about the machinations that go

behind the scenes whenever the Games are staged.

"The politics of it is a different story. Those who contend that there are no

politics in the Olympic Games are speaking with false tongues."

Ask him today if he has mixed feelings about that moment in 1968 when his

salute effectively ended his athletics career and he replies: "I regret the fact

that I had to do that to bring out the truth about a country that didn't honour

the rights of its constitution."

No, he says today, he didn't know that making the Black Power salute was

going to curtail his athletics career. "But had I known, it wouldn't have made

any difference," he insists.

Would he have won more Olympic medals? He ponders the question. "I certainly

would have run. I don't know if I would have been the fastest – but whoever was

ahead of me would have been in trouble!"

'Salute' is released in cinemas on 13 July and DVD on 30 July

John Dominis's iconic photograph is featured in the current exhibition "People Get Raedy: The Struggle for Human Rights" through September 23, 2012