Via Pasatiempo

May 5, 2023

By Brian Sanford

In one image, an older woman sits on a bus, clutching her purse and looking pensive. In another, a man, his face obscured, gazes searchingly into an armpit-high trash bin. In a third, six children congregate in an empty lot with four-story row housing visible in the distance, their faces registering no signs of discomfort.

To observers in 2023, these septuagenarian images by two Photo League members offer candid views of daily life in a handful of American cities, primarily New York, as the shadow of World War II falls away. The images show little of the suffering that’s common in photographs from the Great Depression 15 years prior or the Vietnam War 15 years later. Yet to U.S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark in 1947, the images of real life were sufficiently objectionable to land the Photo League on a list of groups considered “totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive.”

The league was a collective of photographers, many of whom were women or first-generation Americans, who thought their work could improve social conditions in the United States. The collective had endured since 1936 but couldn’t survive the power-mad paranoia of McCarthyism, when a mere accusation of harboring communist sympathies was enough to destroy an association, a career, a life, a family. The league’s placement in 1948 on the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations was the beginning of the end — preventing members from selling their work or getting passports — and it shuttered in 1951.

Sonia and Ida embrace at the Norton Museum of Art in Florida during a Photo League exhibit in 2013.

Courtesy Joe Meyer/Monroe Gallery of Photography

“If you’re wondering what a radical looks like, this old lady here in our backyard, this is what they look like,” Meyer says, pointing to a recent color image of his then-silver-haired mother. “Eventually, they can relax in front of the pond and chill out.”

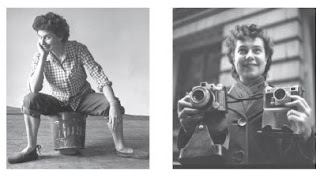

Meyer then shows an image of his mother from her days in the Photo League, her hair still dark as she playfully balances herself while seated on a bucket, shooting the photographer a side-eyed look.

“This is what a radical looks like back in the day, when they were really active,” he says, proudly adding that his mother was born the year the 19th Amendment was ratified, granting women nationwide the right to vote. That was 1920, eight years after New Mexico became a state.

Meyer says his mother continued working, giving lectures and signing prints, until her death last September.

Sonia Handelman Meyer, Girl on stairs, New York City (c. 1946-1950)

courtesy Monroe Gallery of Photography

Sonia Handelman Meyer’s Boy wearing mask features a child tying his shoes while gazing impassively at the camera. In Girl on stairs, a little girl wearing a blouse stands in a stairwell, illuminated by light from the window behind her.

“She loved children,” Meyer says, while showing the audience Children playing in vacant lot, which he calls one of his mother’s most-loved images. ”You know, they’re the hope, and they’re innocent. And these kids, they’re having fun in their vacant lot. There’s no grass, but they’re going to make do, and they’re going to have fun. That touched her, and she captured it.”

Sonia Handelman Meyer had a twin-lens reflex camera, allowing her to look down and see exactly what the images she took would look like once they were developed, rather than having to gaze through a viewfinder and get an approximation. The technological setup allowed her to take photographs without being noticed, her son says, as she didn’t need to raise the camera to eye level.

“She had this like-minded circle of friends; she was kind of left-leaning, as the Photo League was,” he says of his mother’s ideology. “She was anti-war, pro-human rights, pro-women’s rights and equality, you name it.”

She also was afraid — of her government. While the Photo League resisted its demise at first, a member and longtime FBI informant testified in 1949 that the league was a front organization for the Communist Party.

“My parents lived underground in Philadelphia for three years because they were so freaked out, and she was freaked out about the FBI knocking on the door until the day she died,” Meyer says.

Photography funding

Garrison, showing the crowd the only known photo of Wyman’s first camera, says Wyman had to beg her father for the $5 to purchase it. Wyman got an unwanted lesson in overcoming adversity when the camera was stolen at a Woolworth’s store, but she saved enough from babysitting jobs to buy a replacement and joined the camera club in high school.

After graduating at age 17, Wyman had plans to enroll in nursing school but was still a minor.

Ida Wyman, Sidewalk Clock, New York City (1947); courtesy Monroe Gallery of Photography

“She called up every photo editor in New York City and asked for work, and they all laughed and hung up,” Garrison says. “She also called the [Associated Press] and United Press International and ACME Newspictures, and only ACME asked her to come down, but they offered her a job in the mailroom. The mailroom had vacancies because the men were going to war.” ACME was a U.S.-based news agency that operated from 1923 to 1952.

Wyman was promised the ACME role would lead to photography work, Garrison says, but she instead became a printer — an interest maintained throughout her life.

“She began taking photos of children playing in the neighborhood, beautiful buildings with brick, and she just spent time walking around New York,” Garrison says of Wyman’s early career. “She had a talent for connecting with people. As a child I was embarrassed by this, because at every bus stop in New York, she would just strike up a conversation with a stranger.”

As Wyman gained a reputation and clout, she landed a dream assignment for Life magazine. Life, with its wide pages and widespread circulation, focused on photography from 1936 until it ceased weekly publication in 1972.

While doing work for Life was appealing, the subject matter was not. The assignment involved photographing a group of women in Beverly Hills, California, Garrison says.

“Her [takeaway] was that the men doing work for Life kind of got the real assignments, and the women were left with the fluff,” she says.

Wyman stepped away from photography when she had children, as childcare was not financially feasible. By the time Wyman was ready to re-enter the workforce years later, Garrison says, she no longer received assignments and took a job as a medical photographer.

After a cancer scare, she decided at age 57 to rededicate herself to freelance feature photography, forgoing the pension she would have received had she kept her previous job.

“The staff and friends thought that she was crazy for leaving all this behind and going to an uncertain world,” Garrison says. “But she said nothing focuses the mind more than a near-death experience.”

Wyman continued printing in the second bedroom of her New York City apartment well into her 60s, her daughter says.

“I remember that when visitors were coming, we would move the bins of chemicals out of her bathtub so they wouldn’t see this darkroom in her bathroom,” Garrison says.

Wyman took photographs regularly into her 80s, Garrison says — recently enough that she was able to try her hand at digital and cellphone cameras. While she didn’t care for either, Garrison says, she acknowledged the luxury of not having to transport heavy photography equipment.

Sonia Handelman Meyer, Bus Stop, New York City (c. 1946-1950)

courtesy Monroe Gallery of Photography

Gallery owners Michelle and Sid Monroe say 1946 to 1950 was a time of great change in the U.S. in general and in New York City in particular, with an influx of immigrants integrating into an optimistic society.

“We are beginning to describe ourselves as the world’s model of democracy,” Michelle Monroe says of the U.S. at the time. “We saved Europe, we vanquished the Japanese. When you put into context what these photographers’ mission was, that directly contradicted this new description of America. ‘What do you mean, you’re the world’s model for democracy? Look at these children. Look at the conditions that they’re living in.’

“People have been incredulous, asking how these possibly could be deemed threatening. Well, let’s go back to the culture of America post-World War II. They were in direct opposition with the narrative that the McCarthy era was describing. When we explain that to people, they’re like, ‘I got it.’”

Meyer and Wyman met — but not in their Photo League days. An exhibit in New York about a decade ago featured a photograph of them embracing at a museum in Charlotte, North Carolina, says Sid Monroe.

Michelle Monroe adds, “As women, they understood that they couldn’t be pushy, because you know what would happen if you were a pushy woman back then. But they knew how to get things done on the down low, so to speak, and I think that served them well for their entire lives.” ◀

Sonia Handelman Meyer and Ida Wyman: Two Pioneering Women Photographers of the Photo League

10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily, through June 18

Monroe Gallery of Photography, 112 Don Gaspar Ave.

More reading:

The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 (Yale University Press, First Edition, 2011), a hardcover coffee table book by Mason Klein and Catherine Evans, features 150 photographs by Photo League members.